Originally published in Section Culture: Newsletter of the ASA Culture Section. Fall 2019. Vol. 31 Issue 2.

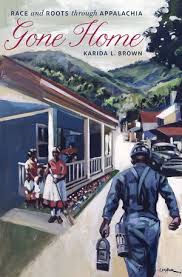

Karida Brown

Gone Home: Race and Roots Through Appalachia

(UNC Press, 2018)

Reviewed by Emily Handsman

Northwestern University

Editor’s Note:

Karida Brown’s Gone Home won the

2019 Mary Douglas (best book) award for the ASA section on Culture.

In Gone Home: Race and Roots Through Appalachia, Karida Brown invites the reader to understand the Black experience in Kentucky’s coal mining towns from what she terms “the standpoint of lived experience” (Brown 2018, 6). She deftly presents a narrative interwoven with broader historical context, specific local history, and the actual voices of her participants as they recount their life stories.

In Gone Home: Race and Roots Through Appalachia, Karida Brown invites the reader to understand the Black experience in Kentucky’s coal mining towns from what she terms “the standpoint of lived experience” (Brown 2018, 6). She deftly presents a narrative interwoven with broader historical context, specific local history, and the actual voices of her participants as they recount their life stories.

Her project connects the macro with the micro: She does not assume her reader has her extensive prior knowledge of Southern history, Black history, or the broader political history of the United States. Instead, she gives her reader all of the details needed in order to properly make sense of the lived experiences she features. We learn the history of the coal industry, along with the history of racial terror in the Deep South—terror that, as Brown describes, pushed Black people to seek a different life in the mountains of Appalachia. While these first few chapters could have simply been relegated to footnotes or appendices as background information, instead Brown uses this macro history to rework multiple historical narratives. First, we come to understand that what has typically been termed the Great Migration should in actuality be called the Great Escape. Brown doesn’t just claim this—she backs this claim up with detailed and persuasive history. Second, we question the quintessential image of Appalachia—while this region is often portrayed as largely white, Brown demonstrates the importance of the Black influx into and then out of this region.

It is not for reasons of rhetorical nicety that I say “we come to understand” rather than “Brown tells us.” Reading this book is a co-constitutive experience—Brown presents her reader with all of the puzzle pieces, and relies on the strength of her evidence and the willingness of the reader to put in some work. This is intentional, as she states in the introduction “the only way I could even attempt to convey the struggle, striving, hope, joy sorrow, and love that they shared in their oral history interviews and through their archival donations was to spill it onto the text and offer this story to you in the spirit in which it was given” (Brown 2018, 8). This is not to say that her intellectual contributions are not clear (they are), but, again, as she notes in the beginning of the book, she places more trust in her reader than most academic texts tend to do, and this creates a powerful experience of discovery and understanding for the reader. Part of this co-constitutive experience exists in the way she presents the data; it is often in large chunks, taking up the most space on the page, at points similar experiences and thoughts are listed together, as if spoken together, by the community. This has a rhetorical effect akin to the traditional Greek chorus—a group voice, speaking for individuals, but together.

She aims to take us “within the veil of the color line” and deftly does so while honoring her participants’ voices and experiences and letting them tell their own stories. This is highly effective writing, both rhetorically, and analytically. Rather than taking the traditional approach of presenting and unpacking one quote and then connecting it to theory, she lets these voices stand alone, only interjecting to make sure the reader draws the connections she intends. In the end, we are rewarded with a tactile and vivid understanding of life in Lynch, Kentucky, in conjunction with deep analysis of the combined effects of structural racism and migration on Black subjectivity. So much of this story is specific to its place, but in its particularity, Brown shows us all what future research of place could look like.

In addition to her dexterous presentation of life in Lynch, Brown uses her case to discuss a few political points that remain just as relevant in contemporary life. First, she demonstrates how the racist regime in Lynch was in part masked by politeness and civility – and she also made sure to show us what happened when the mask came off. Second, she spends two chapters discussing schools as cultural sites. She demonstrates that segregated schools were essential Black community spaces that were disrupted by school integration. This characterization of life after the Brown verdict complicates historical narratives yet again—undermining the argument that anything deemed “progress” has to be universally and exclusively good. Both of these subjects: racism masked as civility and preaching an uncomplicated narrative of progress with no unintended consequences are as relevant in our contemporary political landscape as they were in the 1950s and 1960s.

In her methodological appendix, she discusses the challenges she faced deciding how much room on the page to give to herself, the researcher, the history, and her participants. Her success in navigating this challenge is undeniable, as the reader is left with a convincing empirical extension of Du Bois’ work, as well as an empathetic and truly human understanding of her participants.

Emily Handsman is a 5th year graduate student at Northwestern University. Her dissertation looks at the ways in which suburban school teachers talk about inequality.

You must be logged in to post a comment.